Would I choose to not be autistic?

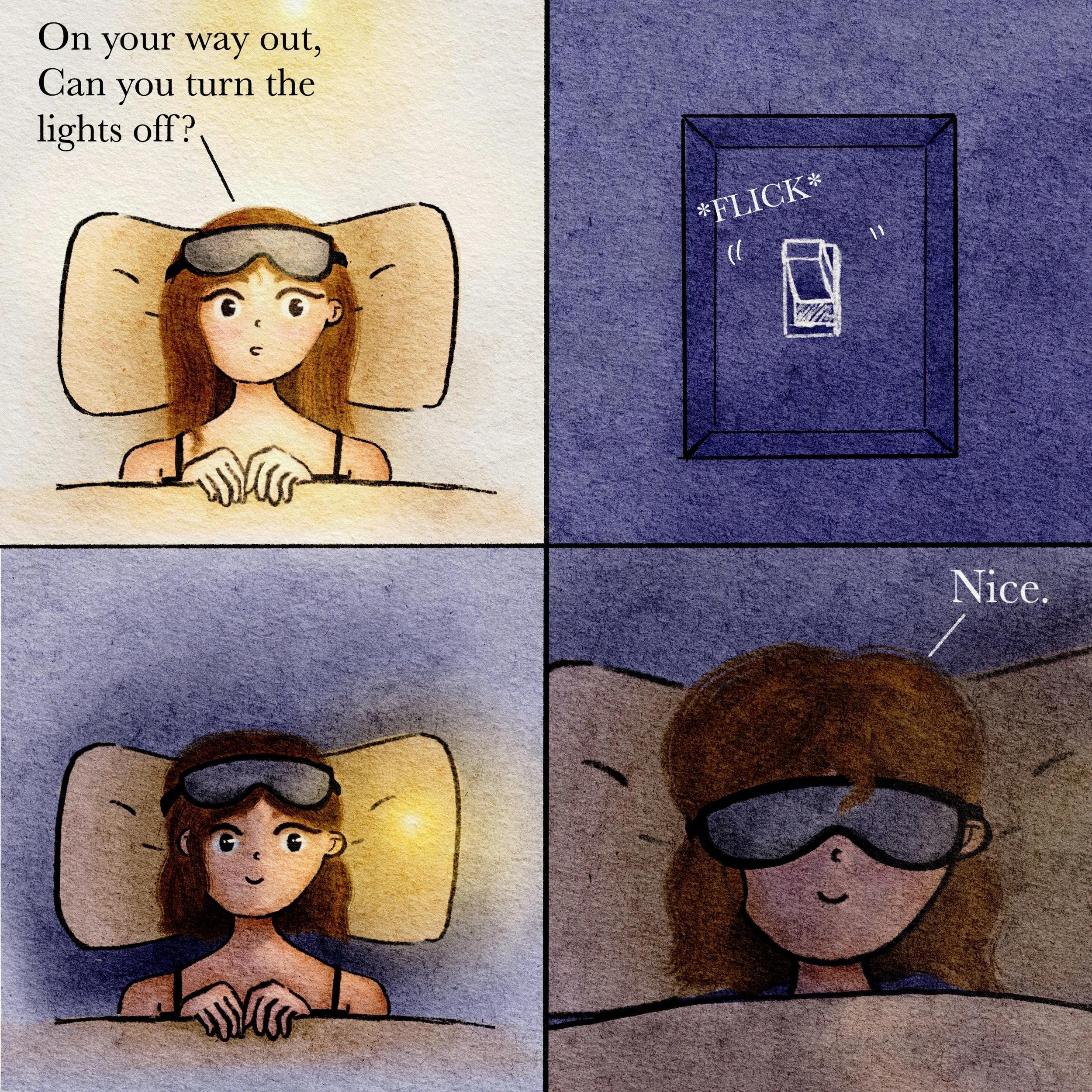

An excerpt from my memoir Can You Turn The Lights Off? ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED APRIl 9th 2024

Dear soft heart,

How was your eclipse season? I’ve been really loving Ocean Pleasant’s takes on astro things lately.

I just finished a truly amazing memoir yesterday called I Am Yours by Reema Zaman, about freeing yourself from patriarchy, eating disorders, rape, abusive relationships, and just wow, so much love. I am learning from Reema as a student right now as well and I feel very blessed to be able to do so - what an incredible story teller. Definitely check it out if you’re into these topics.

Last week, on April 2nd, we had autism awareness day. I like the vibe that it should/ could be called autism Pride Day or autism acceptance day!

I do think a lot of stereotypical versions of autism does lead to a lot of misunderstanding about what a life as an autistic can look like, or even what autism even is and how it affects folks. Of course, I am just one autistic person and my experience is far from exhaustive, but I did write a book called Can You Turn The Lights Off? Based on the most common question I asked due to my autism.

There is an actual chapter in the book, when you get to the almost- very-end that is called the name of the book and it is a very long chapter that talks very extensively about my diagnosis process and shows me wondering things such as, would I choose to be NOT be autistic if I could? I wanted to share this bit of the chapter with you today as part of sharing parts of my book with this newsletter and to celebrate autism too.

If you enjoy it, I strongly recommend you buy the rest of the book right here, as the full chapter does a deep dive into some of the gifts of autism that I feel like everyone should know about and celebrate. If you don’t like it, as Glennon Doyle says, don’t worry about it.

The illustration below is by the amazing Lisa Seilkopf.

All my love,

Emily

Excerpt from…

Thirty-four.

CAN YOU TURN THE LIGHTS OFF?

When you frame my singular autistic experience like this, it’s easy for me to feel grateful I am the way that I am. But I also know some people want me not to be this way. I know what the community of people I belong to have been through; I know this because I’ve experienced some of it myself and because I love to listen to other people’s experiences too. The horrors of ABA therapy, something that is the equivalent of gay conversion therapy in a neurotypical context, make me physically sick. I’ve known it all along, really, even before I had the proper language for it, that I’m a threat to establishments that have outdated traditions. My existence asks for change to occur in the world. I can’t fit it, and people find my stimming disruptive. I’m not made for this world, and I think, honestly, I’m here to help create a new one. Or at least offer another version, just by breathing. I think my medicine is self-acceptance, but it may even go deeper than that. I may also be here, in a spiritual purpose sort of way, to contribute to the world changing into celebrating diversity be the norm. Or maybe that’s what I’m choosing to do with my one wild and precious life.

Of course, I don’t want to glamorize the experience of autism. But I don’t think I do, given that my life stories clearly show that meltdowns are animalistic and then fill you with profound shame and guilt. I have hurt myself, and I have hurt others during its worse iterations. Shutdowns incapacitate me and make my chances at earning a living narrow. Masking is painful and has made me override my consent consistently. Assimilation led me to completely lose my sense of self, which made me believe that everyone knew more about me than I did. Using alcohol and benzos to pretend I was “normal” gave me a slew of other problems. Low theory of mind has led me to form bonds with the wrong people. Over-functioning and being in such high sympathetic dominance for most of my life led me to several different illnesses of which no one could find the root cause.

I think the years of high school and college that I spent studying in the dark made me less skeptical of my autism diagnosis, however. I didn’t struggle much with not feeling “autistic enough.” Sure, I worried that maybe my symptoms were solely due to PTSD, and I wasn’t actually autistic, and I would take up space that wasn’t mine to take up in the disability community. But after your therapist suggests you may be autistic, and you take several valid and reliable psychometrics to confirm this verbal suspicion, it starts to land. After you’ve spent a few years building up the courage to get assessed, and a competent assessor and doctor confirm the whole bit after getting to know you, you feel validated. Then you compare your life experience to your friends who have complex PTSD without the side of autism, and you can clearly see the difference despite the things that may overlap, such as being easily startled, insomnia, and panic attacks.

My superpowers definitely have kryptonite, which is why I have found things like embodiment, somatic experience, and nervous system regulating exercises so effective as someone who experiences hyperacusis, the debilitating thing that makes certain frequency and ranges of sound unbearable, making most usual environmental sounds intolerable. Learning to be in my body has helped me notice when I’m starting to dip past my threshold for sensory information, and yes, that capacity is so small, but at least I notice it now before it’s too late and I’m suffering a meltdown or a shutdown. I’ve also had to put significant effort into introspection to tell when I’m hungry, thirsty, tired, upset, or need to pee. This also helps reduce the possibility of meltdowns because I tend to get them when my blood sugar is low or I haven’t processed an emotion through talking with my mom, my therapist, or writing in my journal.

Before I mastered introspection, though, I struggled immensely with alexithymia. Alexithymia seems to be what most people think of when they think of autism. In fact, I’ve noticed that the current mainstream understanding of what autism is may be better described as an understanding of what alexithymia is instead. It seems like a lot of the general idea of what autism is or is supposed to be or present as, like the person who does not know what they feel or how to describe it or communicate it is called alexithymia and not autism. There is nothing wrong with having alexithymia, but it is not the same thing. Many autistics do have alexithymia as well, but many do not. As of now, I do not score high enough on the Toronto alexithymia scale to be considered to have alexithymia. Therefore, if you think autism is alexithymia, it would not make sense to you when I say I am autistic. Also, neurotypical people can also have alexithymia. So, the more you know, the more being autistic becomes normalized, represented, and properly understood. I started questioning if I had autism and googling about it during a point in teenagehood, simply because my emotions seemed so big compared to other people’s and I couldn’t always pinpoint them or appropriately express them. Not understanding how I felt and having others not understand how I felt made me so mad and frustrated with myself I’d explode and hit myself in the face or bang my head against a wall. Now, I don’t do that. Or if I do, it’s sparse and once in a blue moon. This isn’t curing autism, though. It’s just learning to be attuned to myself and understanding the signals my body is giving me to then communicate to myself and others in my environment what I need to keep myself feeling good.

Sure, there are things like enhanced olfactory detection that may be both a superpower and kryptonite at once. This occurs because my thalamus and insula share more connections than most. This specific brain area is responsible for relaying sensory information, which is probably why I have a heightened sensitivity to smell, sound, and taste. Sometimes, this makes life hard. The smell of cigarettes alone can give me a panic attack. I get woken up if someone across the street starts their car, and I have to keep air purifiers and sound machines on at all hours of the day, so I don’t go crazy as I hear every single crack and sound a building makes. But also, sometimes, this makes life better. Like I can taste things more intensely and I can smell notes and details of dishes, drinks, and desserts that others may not pick up on, and thus I have a more profound experience cooking and eating. I also see colors more intensely. A bland red to a neurotypical may look fluorescent and vibrating to me. This allows me to enjoy art so much more as if I feel its essence, its personality at an intimate level in which only it and I get to know each other. Also, sometimes, the sky is so blue or too gray, it feels offensive to me and too bright, and I need to retreat to my room with my blinds drawn and a t-shirt wrapped around my face in the middle of the afternoon, blow up my autism snug vest, put it on, and lie under a 35-pound weighted blanket.

If I were to be offered a neurotypical existence, a chance to make all the challenges I face as an autistic disappear overnight, including the ones I will inevitably face with age, and as life keeps keeping on, I would certainly think about it. This hasn’t been an easy life. It will certainly not transform into an easy life by magic; there will be no ultimate resolution where I can shake off the “symptoms” that make my life and the life of the people who have to take care of me suddenly blissful. It will continuously demand a creative outlook to be enjoyed. It will require grieving dreams I won’t ever be able to reach. I will always need extra care (whether emotional, physical, or financial), accommodations, and understanding that a neurotypical adult does not need, and probably more as time goes on. I can’t pretend that it has been an overall enjoyable journey with the suicidal ideation and the trauma and the sensitivity that makes someone else’s sneeze feel hurtful. So, yeah, I would think about it.

I’d try to imagine what that would be like. I would wake up in the morning after uninterrupted sleep. I would get ready and not be so tired I’d have to lie down again. I’d go to my 9-5 job or do my work just like it’s no big deal, and I wouldn’t be afraid that everything and everyone was going to be too intense for me because I wouldn’t feel it all in my body as though I am everyone at the same time as being me (synesthesia). I wouldn’t even need to worry that everyone would judge me if I requested an accommodation because I wouldn’t need one. The lights and the smells and the sounds of people would never overwhelm me that much, and I’d still have the energy to go for cocktails with coworkers or make dinner for my family after my day was done. I would go shopping and not think twice about it. Maybe I would even go to a group workout class with loud music and fluorescent lighting I have no control over and plan baby showers for friends or attend one of those weekly brunch gatherings. I could follow self-help and mainstream psychology advice, and it would actually work for me because they’re all made for neurotypical and not autistic folks. I’d have an easier time with dating, and I would be able to decode someone’s intentions right away without confusing my own with theirs. No one would call me aloof or be mad at me because I did the thing where I disappear again and don’t answer my phone for a few days because I’m too overstimulated or because I’m doing that other thing where I can’t let something go and I keep ruminating. I could have kids without worrying that I wouldn’t measure up for them because of disability or worrying that being over touched by them, even if I loved them, would probably lead me to a mental breakdown. I could go to school and do a bunch of education because I love it and not agonize about requiring any “special treatment” that would possibly and most likely be scrutinized by peers and teachers alike and make me feel like an outsider who doesn’t belong. There would be so much I could do and have if I was neurotypical that I can’t do now. And I think the most attractive possibility in all of it is the better sleep situation.

But I also would be scared to be anything but autistic because of the extraordinary things it allows me to do. My favorite parts about myself are possible because I am autistic. Society may not put a value on some of my makeup, may consider me as disabled because I can’t be able in the way it wants me to under the circumstances that are demanded. Still, I recognize also what a true privilege it is to be autistic. What a privilege it is to be so open and so conscientious.

Yes, I’ve been told I’m so mysterious or hard to read, and I’d love to say it’s because I’m a Scorpio rising. Still, it’s probably just because of my occasional reduced affect display, which means that, compared to a neurotypical, I’ll have a reduction in emotional expressiveness due to lack of facial expressions that would be appropriate to the normals or because of vocal inflection. It doesn’t mean that inside I don’t feel many things; it simply means that sometimes I forget to emote what I feel inside on my face or in my voice if I’m not masking. Autistic individuals are notoriously hard to read, which can make some people uncomfortable. So, yes, exactly, I’ll always have to try so much harder to be understood, to fit in, so I don’t get picked on for the barrettes I love to wear that make me look like an alien, and the weird clothes I keep wearing every day, and the fact that I get obsessed with one recipe and make it on repeat. Yes, my intensity will most likely always stand out to others. I’ll never be as extraverted and agreeable as the majority of people. I’ll always be neurotic and have a hard time tolerating stress. I’m aware that most won’t find me easy to deal with. I’ll most definitely be remembered as picky and difficult and perhaps even controlling. I know my legacy won’t be, “Wow, Emily was so chill all the time!”

But would I want to be any different, like truly? Permanently?

No, I don’t think I would. This is why I’d decline the opportunity to be. And this is why I’ll always continue to fight to remove ableism from our society through my writing and my advocacy work in my programs, in interviews, in everything I do, so that we can all arrive here, at this heart-exploding, throat-tugging, slight tear-inducing acceptance, and celebration—for ourselves and for each other.

Brains of neurodivergent people differ more from the brains of neurotypicals. This is why the saying goes, “If you have met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.” This is also why no one autistic can accurately speak for all autistics.

Some things of the typical universal autistic experience I’ve never lived, like the difficulty recognizing or memorizing faces. It’s true I memorize people’s hair more, but it’s never happened to me that I couldn’t tell which kids were the proper ones I had to pick up from school when I was a babysitter. But this doesn’t make me less autistic. It just means my specific neurodivergent brain doesn’t struggle with that, just like someone’s else neurodivergent brain may not experience mirror-touch synesthesia or have such pronounced sensory sensitivity as I do because they don’t have hyperconnectivity in that part of their cerebral cortex. Someone may experience more social differences than me, for example, and have a harder time reading facial expressions on their loved ones than I do. I don’t struggle much with knowing how someone else feels or showing empathy “appropriately,” for example. One person’s neurodivergent experience may include intellectual disability, while another’s may not. It’s called a spectrum for that reason. We all have our own experiences of being neurodivergent human beings, even though we share common traits and similarities. This means we all have differing levels of needs. We shouldn’t be counted as more “valuable” if we have less of them. It’s incredibly ableist if someone says to me, “Well, you’re lucky because at least you’re high functioning.” Or if I’m asked, “You have Asperger’s, right? That’s the smart kind of autism, yeah? Thank God you don’t have the other kind.” And, in the same breath, it’s equally as ableist to assume that I don’t have acute challenges and that I can and should just get on with it as though I’m not disabled.

Yes, I can speak full sentences and present as intelligent, friendly, insightful, and perhaps more “socially docile” and proper in a neurotypical way than someone who would be diagnosed level 2 or 3 on the spectrum. Indeed, this gives me more opportunities in this society. Absolutely, this puts less strain on my caregiver. But just because I can mask doesn’t mean I can function as though I’m not autistic. I cannot bypass that I’m autistic. I tried. It didn’t work. I became an addict. I got very sick. I nearly died.

So, there is a difference between me versus the mass majority of the world; I can’t deny it. However, there is also sameness. Neurodivergent or neurotypical, we are all individual and different people who are influenced by things outside of our control that we didn’t really choose, but that became part of who we are. Like how our parents raised us, the kind of society we found ourselves in when we were born, the schooling system we were placed in during the decades we attended. I am a sum of those things. We all are.

So, I guess the autistic life experience may just be an experience of life just like any other—unique, unrepeatable, our own moment in human evolution we get to decide what we do with given the cards we’ve been dealt. There are some great things about it, and there are less than good things about it. I’ve made mistakes, and the people around me have made mistakes. I’ve experienced joy and success, and I’ve experienced heartbreak and disappointment. Maybe we’ll never know in our lifetimes if we can all get along and stop trying to make people who don’t fit the cookie-cutter mold of who you’re supposed to be as a human being feel like they’re a burden and don’t deserve as much pleasure and belonging because they can’t produce at a level that allows them to slip into norms of capitalism where the lights are bright and the hours are long. I truly don’t know if we’ll ever stop judging a fish by its ability to climb a tree, but I hope we do because the fish isn’t stupid or useless; it’s just not a squirrel.

Maybe I’ll never see this change happen while I’m alive. But I’ll work toward it. Regardless, on your way out, can you turn the lights off?

If you liked this snippet of my memoir Can You Turn The Lights Off?, here’s where you can buy it and hang out with me for roughly 400 pages and exactly 36 stories- https://emilybeatrix.com/thebook