Writing about trauma is delicate

But we can do it with trauma aware storytelling :: ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED APRIL 24th 2024

Dear soft heart,

I began writing a new book about a month ago. It is my debut fiction. I have not written fiction in 10 years - it was something I felt I had to completely abandon because I needed to pay my bills. My mom encouraged me to join, and then signed me up for a writer’s group where I’ve been learning so much. When I think back to my favorite subject in school, it is always without a doubt, writer’s craft.

Once our teacher blindfolded me and brought me outside to the forest behind our school and nurtured my feeling writing - if you can’t see, what are you noticing? She asked me. She made us tea and asked us about our lives, and every time I wasn’t at school, she would slip me the papers I missed without anyone else noticing. She was the kindest adult I knew outside of my mom.

I am really excited about it, beginning my debut fiction, and it has given my life some meaning again. I plan to send out query letters, find an agent who falls in love with the story, and all that jazz.

I went dark there for a few months in the throes of very intense severe autistic burn out, which I am finally feeling ready to share about sooner rather than later. I’m still in it, thus, I am very careful with my self and have very little spoons still, but I am currently mapping my life throughout the different burn outs I have had, making data on it all because I want to share my case study with you. I learn a lot from the generous sharing of experiences from my favorite writers, so I want to offer the same. I am fascinated by what has thrown me into burn out the 3 times I have experienced it so far in my lifespan. And I am equally interested in pin pointing also what has kept me out of it when I could have easily slipped into it.

I am also sitting with the very dark reality that this burn out has seemingly (time will continue to tell), permanently made me lose skills that I had previously. This has affected my daily functioning in really hard ways, and has upped my need for care. It’s a lot to accept and wrap my head around, but it is a reality for a permanent, life-long, disability like autism. Autism often becomes more challenging as we age. We have all sorts of terrible stats that tell us about our average life. I am having to mature in understanding some of this more readily, rather than avoiding it. Anyway point being for now, my life has changed greatly in the past year - since my last birthday - which is about to come back around in early June. I am having a hard time accepting it, these changes, but I am working on it and writing about it as I explore the topic of autistic burn out to share with you on this newsletter, and it is helping me make sense of things. I’m looking forward to sharing it with you.

In writer’s class this week, we talked about writing in present or in past tense. Both create different outcomes for the text and for the reader. I chose to write my memoir mostly in past tense, with me of present day as the narrator commenting and critiquing on my protagonist life’s (myself for approximately the first quarter of my life). When we write in past tense like this, it allows us to have a voice of wisdom.

I felt I needed to write in this tense in my memoir because the point of it was that the protagonist starts off in two worlds and journeys all the way to only living in one. She’s got these experiences that leave her feeling like she can only be herself half of the time, and then she journeys her whole life thus far, to arrive at a place where she is only living in my one world. One where she does not have to mask, modify, hide, be confused about herself, the world around her, or feel misunderstood or told who she is by everyone else, rather than declaring it to them because she knows herself and can’t be defined by the world. Actually, she can only be defined by herself. The first chapter is called Two Worlds and the last chapter is called One World - that is the arc of my first memoir.

Since I was writing a lot about heavy topics in this book, I felt like if I stuck to writing in the present tense, there wasn’t enough perspective on the events that happened and I could not show the growth the protagonist earns from the events she lived. Even though, yes, writing in the present tense can and does allow for more embodiment, I didn’t choose it as my main tense. I felt also that the reader would get just as overwhelmed as I did actually living my life if I did not have some sort of higher perspective guiding the story.

I think I was right about this, because I have gotten some feedback that it’s heavy to read in some places - and this is with a narrator that is comforting throughout it. Writing about trauma is delicate in this way. Not everyone wants to read about it - chances are actually, most people won’t want to. And for those who are survivors who are reading, some scenes can be too triggering even though they are extremely validating - so how do we strike a caring and helpful balance - to show the experience to create connection, but also tell it in a way that is not going to re-traumatize, and ultimately cost us that connection? Like for example, I chose not to write the play by play of my rape scene. Instead, I wrote about what the feelings of the aftermath of rape are/were. A lot of readers told me that this is one of their favorite chapters since the book was published citing it’s done really well in the writing. I taught classes in 2021 about trauma aware storytelling and I really enjoyed exploring this with students.

Not writing our trauma holds us back from integrated lives and to be honest, we hold each other back too if we don’t write our trauma. We need to be mirrored to each other to feel a sense of belonging, and, there’s a way to do that that is accessible without being too precious about it too. I know a lot of people feel that storytelling is becoming increasingly too censored - that we have too many trigger warnings and that we cannot tolerate other perspectives than our own, which is definitely culturally important to look at and analyze from a nervous system perspective as well in my opinion.

It was a tough choice to make as a writer, which tense to use while writing about trauma, and sometimes, I would go to present tense to give some dialogue to illustrate a dynamic that only present tense could offer the reader. In those moments, I wanted to create that intimacy specifically between the characters in the book, and between the protagonist and the reader. After that, I would swing back to past tense with that perspective again from the POV of the narrator - wise me who has survived all of this and healed.

It was really important to me to have the narrator possess the wisdom of surviving the experiences and have the power that comes from the authority of having already alchemized them.

I added so much compassion, love, grace, forgiveness as the narrator of my memoir comments on the protagonist’s actions, life, emotions, decisions, regrets, thoughts, that would not have been possible if I was writing from the present.

My teacher Reema Zaman, says that “There is only so much we can control in this life. Writing is a healthy form of control. You can go back to have agency.”

Exactly. With the perspective of the wise self in Can You Turn The Lights Off?, there is a collection of moments that get to be understood and seen differently than when I first experienced them. There is a reclaiming of agency in this.

I am also simultaneously doing the artist’s way for the 3rd time - this time, for the first time with my mom and my writer’s group. We are at week 3, recovering a sense of power. I love this week in the book, especially the part on shame.

Putting out my memoir into the world really was hard on my nervous system. I feared retaliation, I feared getting in trouble, I feared all sorts of things… In retrospect, I was afraid of being shamed. I was also doing quite a bit of self-shaming at the time that wasn’t immediately evident to me. I knew I would have to stretch when I published it, to cultivate safety, but I did not anticipate how much I would be triggered, and dealing with my wounds. I had wished that the hard work, the writing of it, was all there was to it in terms of lessons and growth. Of course, the publishing process also initiated me into deep healing.

Julia Cameron says this about shame:

The act of making art exposes a society to itself. Art brings things to light. It illuminates us. It sheds light on our lingering darkness. It casts a beam into the heart of our own darkness and says, “See?”

And…

By telling our shame secrets around our art and telling them through our art, we release ourselves and others from darkness. This release is not always welcomed. We must learn that when our art reveals a secret of the human soul, those watching it may try to shame us for making it.

I find this said clearly so liberating. It reminds me again that should my biggest fear happen, being shamed, it usually comes from this place. It’s not because I am bad, or wrong, or horrible.

Now I am writing my fiction in the present tense and I really appreciate that because it is allowing me to create this very embodied intimate experience of the protagonist’s world. Her name is Dorothy. She is incredibly self-aware and aware of her environment and of people, but she is also devastatingly lonely, in grief about her sister’s death, surrounded by emotionally unavailable parents, jealous of people, even her closest friends, and in need of companionship and this is where she experiences a main conflict - the pull between being aware and smart, and the crushing reality of her human flesh needing love she doesn’t have access to. This is the ground she is standing on when she falls for an abusive relationship that changes her life forever.

I don’t feel this pressure in the fiction to have a very healed take on everything in order to present it which is giving me so much more creative freedom to explore writing about different traumas. It helps also that Dorothy is not me. What she thinks or does, isn’t always what I would think or do, and thus I can explore feelings and take them to places I would not be going myself or perhaps wouldn’t dare to go, either. It’s exhilarating. It’s cathartic. When I was writing memoir, which I will for sure write again in my life, it was extreme emotional labor.

An early reader of my memoir, Hayley, so graciously told me that it was amazing the perspective I was writing from. I had so much to be angry about, yet I wrote with this truly loving take. That was very intentional, but it was also hard earned. I truly did all that work on understanding and on loving, and on forgiveness and on boundaries and on grieving and on rising from the ashes of developmental trauma and finding freedom.

One of my most treasured feedback from the memoir has been how restorative it is in terms of justice and how nuanced I managed to make all the characters, including myself. I write about my father with so much understanding, forgiveness and love, even though he hurt me really badly.

When I have made mistakes myself, or hurt people, I write with honesty but I also forgive myself and understand myself too.

I think it is really easy as a protagonist in a memoir to always stay in the role of the hero, and I thought that as the narrator, with perspective, I could also challenge the idea that we exist in binaries of protagonists and antagonists. There are no heroes and no villains in my memoir. We are all much more complicated than that. Yet, there is also deep protection, realistic insight, and boundaried love that the narrator offers the younger self, and the current self by the end of the 400 pages.

It was my hope that by writing this way, I could encourage the reader to internalize this way of relating to themselves and also to the people they’ve been in relationship with.

In this memoir, for me, I didn’t want it to be self-helpy, but I still wanted it to lead the way to somewhere new. I think I managed to do that, because I’ve gotten a lot of feedback that it feels like I am guiding people home to themselves, but without actually giving any overt instruction. It’s all just shown in the way that I relate to myself through being the wise narrator as I critique the protagonist’s first quarter of a century on earth, as she comes of age.

It is showing, not telling, how to take care of oneself post trauma, as an neurodivergent human. There are no lists or guides, just an insight into a loving relationship with self that can serve as a model if you’ve never seen one.

After all, we make the art that we once needed the most, don’t we?

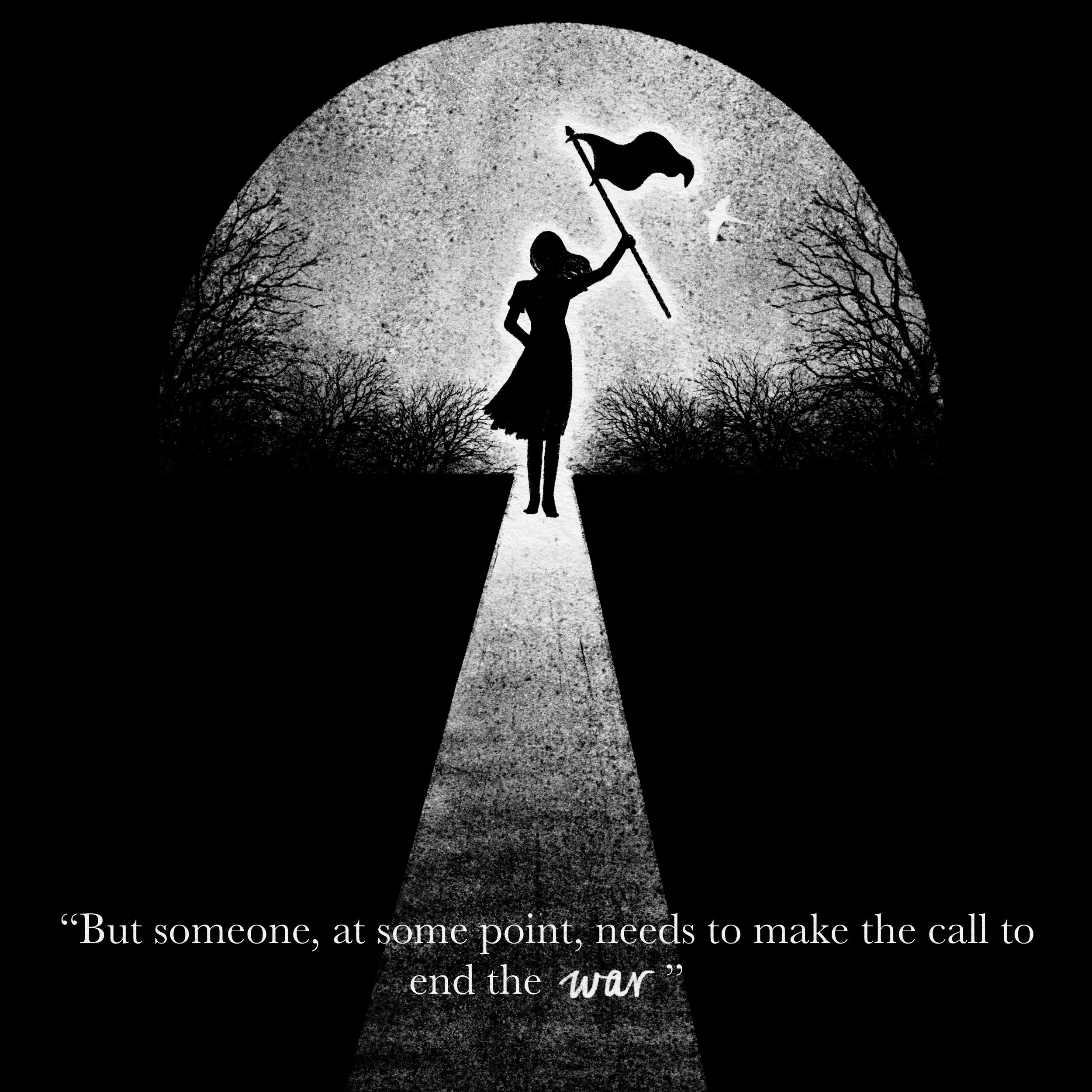

In chapter 12, The War, I use war and the aftermath as a metaphor for developmental trauma and how it affects each child differently. At the end of the chapter, I write, to showcase the point that we have a choice as survivors of developmental trauma if we are still alive, will we continue to externalize or internalize the abuse we’ve lived, continuing the patterns downward through generations, or outward towards our social circles and toward our existing relationships, or inward, killing ourselves with hate and shame and things that weren’t ours to begin with? Or will we do the only thing we can do other than perpetuating this pain - something different.

When I feel that weight, like it’s all up to me again, I have to force myself to remember I did not, we did not cause this war. I did not send us out there onto those battlefields. I did not choose the developmental trauma we underwent. The people who chose this for us were the same people who did not fund the hospital bill or the rehab center fees. They were the ones who did not send flowers or come sit by my bedside. As much as it would be easy to blame my mom or my dad entirely, it wouldn’t be accurate or fair. They were born into this whole thing too.

Because one thing the war has taught me is that if we’re going to blame, we have to blame intelligently. That means let’s look for those who started this whole thing; let’s give them back the responsibility and the karma. Let’s do the only thing we can do as survivors who have access to a better future: be where the dysfunction ends. We may not have caused the wars we were born into, but we can have a hand at not making any of our own. That, to me, is recovering from developmental trauma, which I think is a lonelier and much harder road than you’d expect. But someone, at some point, needs to make the call to end the war.

Which Lisa Seilkopf illustrated in this image…

I am sitting currently with the fact that there is so much I cannot change in my life. In my teenage bedroom, I had a wooden engraved sign that said the serenity prayer, “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference.” I have clearly been sitting with this for a long time. There is so much that we cannot change. Similarly, there is actually a lot we can change. Sometimes I wonder if my effort to heal even matters, or if things I cannot control will constantly dominate me into crisis, or if my autistic brain and body make me completely doomed in this society (they sort of do). And beyond that, the free will of other people can be so infuriating to navigate for us all. In those moments of frustration, I remember what I have in my lane to focus on. Who do I want to be amongst all this?

If you are interested in buying my memoir, you can do so here.

I really thank you for being here and enjoying and/or supporting me as a writer.